SONIA DELAUNAY

Sonia Delaunay (1885-1979) is a celebrated figure in art and design history, synonymous with the Parisian avant-garde. Alongside her husband Robert Delaunay (they were something of a power couple on the Paris art scene), she developed a theory of ‘simultaneous’ colour contrast that she expressed not only through painting, but in bold and beautiful pattern designs.

Delaunay started life in Ukraine as Sara Elievna Stern, before being sent to live with her affluent relatives in St Petersburg, where she adopted the name Sonia Terk. A cultivated couple, her aunt and uncle introduced her to the art museums of Europe, kindling her fascination with painting.

Sonia Delaunay and two friends in Robert Delaunay’s studio, rue des Grands-Augustins, Paris 1924. Image Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Venturing to Paris in 1905, the young Sonia immersed herself in the thriving art scene, studying at the Académie de la Palette and frequenting exhibitions. She entered into (by all accounts) a marriage of convenience with the gay art dealer Wilhelm Uhde, who helped her exhibit her paintings for the first time and introduced her to leading artists such as Matisse and Picasso. The marriage ended shortly after Sonia fell in love with fellow painter Robert Delaunay in 1910 - this was the start of an intense and prolific relationship, not only as lovers, but as creative collaborators.

The couple were ardent promoters of abstraction in art; their paintings are typified by concentric circles, rainbow-like arcs and rich colour. They pursued colour theory, influenced by the ideas of Michel Eugène Chevreul, and proposed their own theory of Simultanéity, sometimes also referred to as Orphism.

The Minho Market by Sonia Delaunay, 1915. Glue and gouache on canvas. Image Sotheby's.

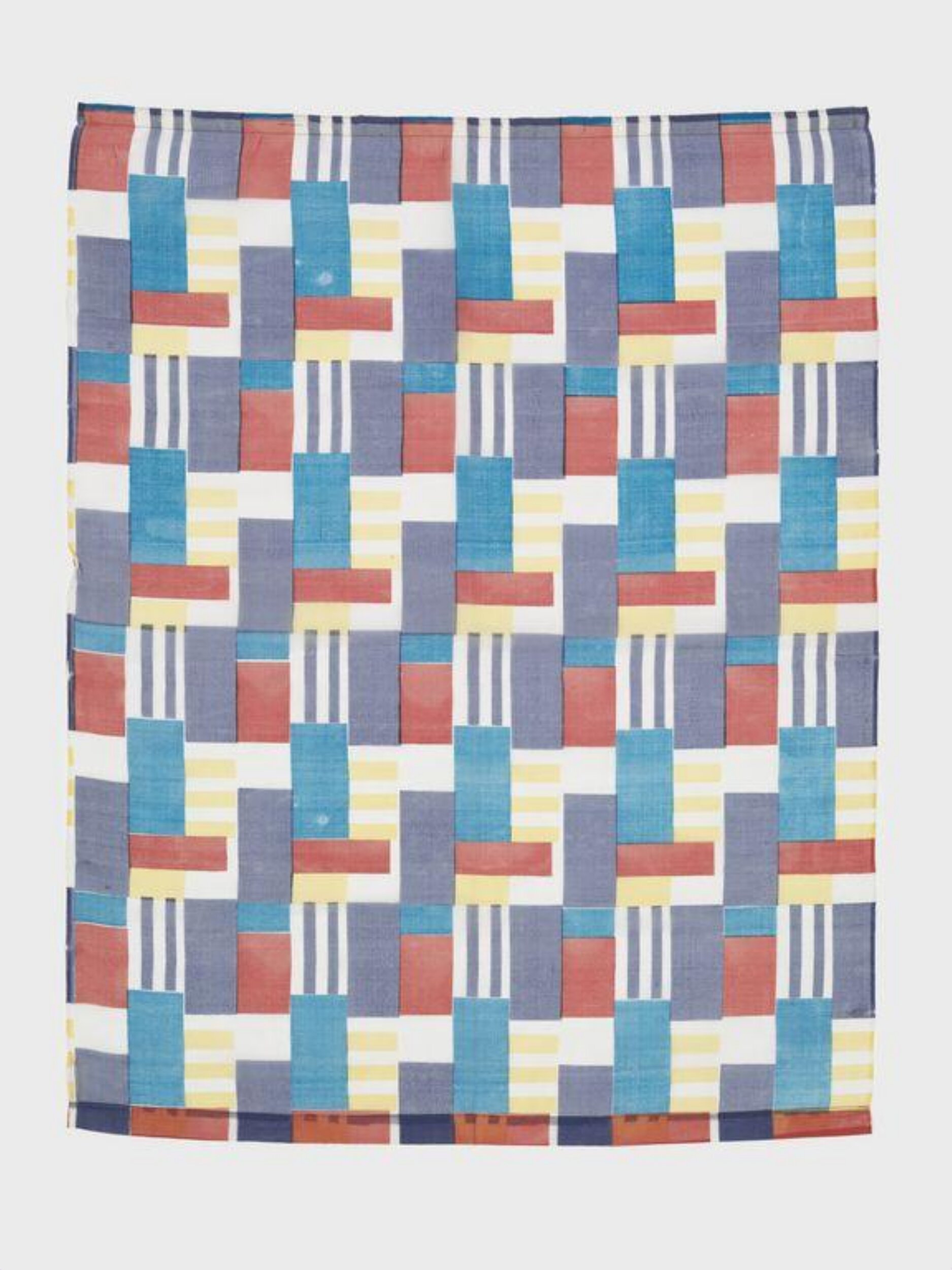

Left: Dress fabric of screen-printed silk organza, designed by Sonia Delaunay 1925-1927. V&A.

Right: Sonia photographed by Florence Henri, 1934.

The period between 1910-1940 was one of great cross-pollination between the once-distinct fields of fine art, design and craft in Europe. Delaunay absolutely embodied this boundary-breaking approach. From the outset of her career she utilised fashion, textiles, ceramics, interior design, printmaking and typography to express her visual ideas. She even collaborated with several Dada poets, transcribing their words into fashion designs known as ‘dress-poems’ (now if that doesn’t say ‘avant-garde’ I don’t know what does).

Delaunay had an entrepreneurial spirit. She opened several businesses across Europe to promote her work - Casa Sonia (1918), L’Atelier Simultané (1924) and Maison Delaunay (1925) - each dedicated to the production and sale of her fabric, fashion and furniture designs. I would have loved to have visited one of her boutiques - I can just imagine the boldly printed silk scarves draped against a backdrop of colourful murals.

“Everything she did was as modern as jazz.”

Pochoir printed plates from 'Ses peintures, ses objets, ses tissus simultanés, ses modes', 1925.

Perhaps my favourite pieces of hers are the 1920s fashion designs, printed using the pochoir process (pictured above). There's almost no distinction between her fashion designs and her paintings; the quintessential blocks of colour, circles and chevrons create thoroughly modern costumes (don’t forget, only 20 years prior many women were still dressed in stiff Victorian garb). As Diana Vreeland says, “Everything she did was as modern as jazz.”

During her lifetime, Sonia’s creative achievements were somewhat overshadowed by her husband’s - only in recent decades has her work been celebrated independently of his. As she stated herself in 1978, one year before her death: ‘What had people been saying about me up to then? – muse of Orphism, decorator, Robert Delaunay’s partner. Then they conceded: “collaborator, continuer…” before admitting that the work existed in its own right.’

Sonia in her studio c.1967